How Heather MacTavish Found Her New Rhythm

In this thought-provoking essay about her experiences with Parkinson’s, Heather MacTavish lays down what fundamentally, makes us all human, and how we share so many of the fears and excitements in this illusion called life.

Personal Stories, Shared Perspectives – An Essay

As my neurologic functioning declines, I find myself more and more preoccupied with questions surrounding concepts of responsibility and reality. One does not immediately plunge into a world governed by medical labels such as dementia, Parkinson’s, or Alzheimer disease—never to return. It is rather like being repeatedly immersed in an uncertain sea. At times, I float serenely over the water. Sometimes I am tossed on top of waves of excitement and purpose. Other times are the drowning times, when I find myself going under, certain I shall never again rise.

During the surges, plunges, and lulls in the storm of my existence, I must constantly monitor my actions and reactions. I struggle to observe myself in an effort to predict and prepare for the next wave. This laying down of new perceptual paths involves confrontation with my sense of self—my place in the world; as my friend Edith would say; my ‘ness. The old ways and the responses that served the needs of my past are constantly beckoning, tantalizing me with a promised easing of hard work. I find myself questioning my attempts to reweave my personal reality, doubting, wanting to retreat under my blanket of familiarity, thumb rooted securely in my mouth. Instead, I ponder, wandering through murky memories, entering the vault of my perceptions, venturing down corridors leading to new doors of understanding.

What influences my pensive nature? What drives my passion for communication, connection, and understanding? My life and philosophy have been nurtured by circumstance and choice and have provided opportunities for rumination, exploration, and growth.

In 1996, Parkinson’s disease was in the nether world of my perceptions, vaguely connected to boxing, Mohammed Ali, and blows to the head. At forty-six, the blow of the PD diagnosis was a hard hit into the soft underbelly of my very being. Initially stunned, I retreated into a familiar world of books and research. I was determined to find an understanding and a solution to the ravages of this “old” person’s disease.

Instinctively, I started dancing at night; suffused with music, shedding articles of clothing until there was nothing between me and the 3 am pulse, soaring with the songs, revelling in fluid movement—in ecstasy. As I danced, I found myself in concert with my body. Stumbles became graceful sways. My leg that so often dragged behind joined in the dance. Pain was replaced by passion. There was little room for fear during those flights of feeling and abandon.

Passion has always been the propellant in my life, fuelling adventure, mitigating adversity, and pre-empting pain. Passion could not, however, overcome the devastation of the Parkinson’s diagnosis—certain death to my life as I knew it. I prepared for my journey into nothingness.

I closed my business and bought a harp that became the object of my tactile and auditory pleasure. Having never played an instrument and unable to read music, I yearned for pleasure, not proficiency.

My abilities to learn new skills, remember instructions, and write, were already compromised when I met Lynn Michaels, a talented and empathic harpist and teacher. Compassion and gentle acceptance were the special gifts she brought. What Lynn did not bring were also gifts. She brought no judgments, no rules, and no predetermined lesson plans. I played my harp, comforted and transported by vibration, tone, and touch. I was storing memories.

A year later, I stumbled (not a surprising movement for one affected by symptoms of Parkinson’s) on Phantoms in the Brain by V.S. Ramachandran. His book had a profound impact on me, demonstrating and inviting a sense of humour and willingness to ‘just see’ what might happen. I decided to experiment, intent on rewiring my brain, focused on the possibility of creating new neural networks to replace those that were becoming more and more elusive.

My body became my private laboratory for yet another field of study. I began a new major in neurobiology and brain plasticity. As I explored, I discovered drumming. I bought a drum with a rich and resonant voice, forgiving of my erratic strokes.

My arm gained mobility in a metamorphosis so subtle that I was unaware of the small changes occurring. My spirit and physical health improved. I began peeking through the once-closed fingers of fear that were covering my eyes and saw signs of spring beckoning me to emerge from my chrysalis.

I began to share the joys and benefits of drumming with residents at a local retirement community and discovered an astonishing new life filled with individuals who have extraordinaire-abilities and, like me, deal with physical, neurological, and emotional challenges. I had found a new family. We share issues of ageing and loss. And we share delight

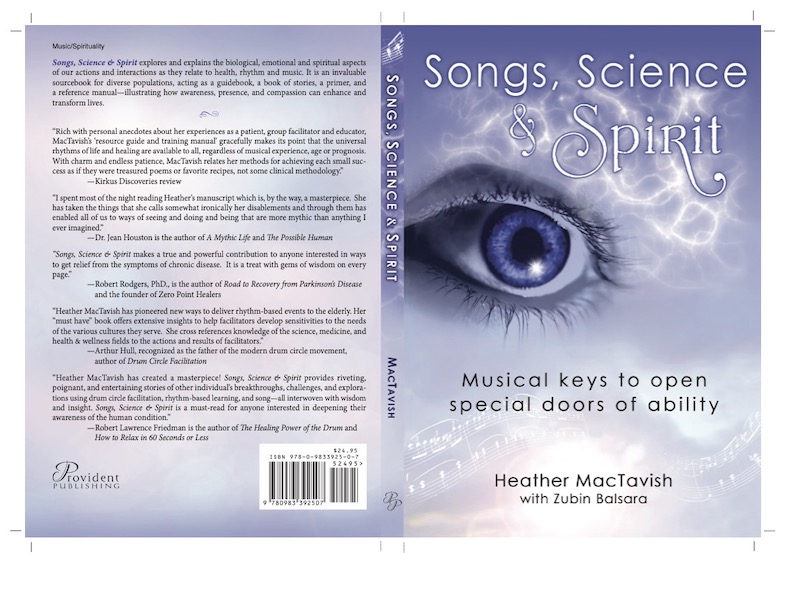

– Heather MacTavish (2007) Excerpted from “Songs, Science & Spirit”.